How to Value a Business for Sale in Australia

When you’re ready to sell your business, the first and most critical question is always: “What’s my business actually worth?”

It’s tempting to pick a number that feels right, but a true valuation goes much deeper. It’s about understanding the real, defensible value you’ve spent years building. Getting this figure right is the foundation of a successful sale, setting a realistic price and giving you a much stronger hand when it comes to negotiation.

Establishing Your Business’s True Worth

A professional valuation does more than just give you an asking price. It provides a solid, evidence-based foundation for every conversation you’ll have with a potential buyer. When you can back up your price with clear financials and recognised valuation methods, you move the discussion away from opinion and onto solid facts. This builds enormous credibility and puts you in the best possible position.

Core Valuation Principles

In Australia, valuing a business isn’t guesswork. It’s a structured process based on established principles to arrive at a fair market value. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) also has its own guidelines, so getting it right is crucial for compliance. Think of it as building a robust case for your business’s value.

There are three main ways to approach this, and the best one for you will depend on your industry, size, and business model.

- The Income Approach: This method focuses on your business’s ability to generate future profits. It’s the preferred method for established, profitable businesses with a reliable track record of earnings.

- The Market Approach: This is much like valuing a house. You look at what similar businesses in your industry have recently sold for to establish a benchmark, using market-based multiples.

- The Asset-Based Approach: This is most common for businesses where the value is tied up in tangible assets, like a transport company with a large fleet or a manufacturing plant. It’s a straightforward calculation of the company’s assets minus its liabilities.

A valuation is only as strong as the evidence supporting it. It transforms your asking price from a hopeful figure into a justifiable business proposition, giving you leverage during due diligence and final negotiations.

Often, the most robust valuation comes from using a blend of these methods. This gives you a comprehensive picture of your business’s worth, ensuring the final number is not just accurate but can stand up to the scrutiny of buyers and their advisors. It’s the essential groundwork for your entire sales journey.

Getting Your Financials Ready for a Buyer’s Eyes

Before anyone can place a realistic price on your business, your financial records need to tell a clear and compelling story. Think of it as a crucial first impression for a potential buyer. This isn’t just about having your numbers in order; it’s about presenting the true picture of your business’s ongoing profitability.

This process is known as ‘normalising’ your accounts. It’s all about filtering out financial ‘noise’ to show a buyer the business’s standalone earning power.

Getting this right builds incredible trust. When a buyer sees clean, normalised financials, it shows transparency and a deep understanding of your business. It’s the difference between a confusing P&L statement and one that clearly justifies your asking price.

Why You Need to ‘Normalise’ Your Accounts

If you’re like most small business owners, you have likely structured your finances to be tax-efficient, not to impress a potential buyer. That’s just smart business sense for day-to-day operations.

However, a buyer needs to see the business’s profitability from their perspective, not how it was set up for your personal tax situation.

Normalising your accounts means making specific adjustments to your profit and loss statement. The goal is to arrive at a repeatable, ongoing profit figure that a new owner can reasonably expect to achieve. This is often called Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) or, after adjustments, Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation, and Amortisation (EBITDA).

It’s a bit like staging a house for sale. You’d remove personal items so buyers can imagine themselves living there. Normalising your financials does the same thing—it strips out personal and one-off items so a buyer can see the business’s true potential.

Sorting Out the Owner’s Salary

One of the first and most significant adjustments is your own salary. Many business owners pay themselves a minimal wage, taking the rest of their income through dividends or director’s loans for tax purposes. It’s a common and legitimate strategy, but it understates the real cost of running the business.

A buyer will either have to run the business themselves or hire a manager to fill your role. That’s why your reported salary needs to be adjusted to reflect a fair market rate for the job you actually do. For example, if you pay yourself $50,000 a year but the market rate for a general manager in your industry is $100,000, then a $50,000 adjustment is required.

This simple change provides a much more realistic view of the business’s labour costs, ensuring the final profit figure isn’t artificially inflated.

Finding Personal and One-Off Expenses

Next, you’ll need to go through your expenses with a fine-tooth comb, looking for anything a new owner wouldn’t have to pay for. These are known as “add-backs”—expenses that are added back to your profit because they aren’t essential to the day-to-day running of the business.

To help you get started, here’s a look at some of the most common adjustments we see.

Common Adjustments to Normalise Your Profit

| Adjustment Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Owner’s Salary Adjustment | Adjusting the owner’s reported salary to a fair market rate for their role. | The owner pays themself $40k, but the market rate for a manager is $90k. Add back the difference. |

| Personal Vehicle Expenses | The portion of motor vehicle costs (fuel, insurance, rego) used for personal, non-business travel. | The company ute is also the family weekend vehicle. A percentage of its running costs is added back. |

| Family Member Salaries | Wages paid to family members who don’t have a genuine, active role in the business. | A spouse is on the payroll for $30k but doesn’t work in the business. Their salary is an add-back. |

| Discretionary Spending | Personal or non-essential expenses run through the business, like personal travel or entertainment. | That “business trip” to Bali, or personal meals claimed as ‘entertainment’. |

| One-Off/Non-Recurring Costs | Significant, unusual expenses that a new owner is unlikely to face again. | A major legal bill from a one-time dispute or a large, unrepeated repair cost. |

| Excess Superannuation | Super contributions made for the owner above the standard superannuation guarantee (currently 11%). | The owner contributes 15% to their super. The extra 4% is an add-back. |

| Interest & Finance Costs | Interest paid on loans is typically added back as a buyer will have their own financing structure. | Interest payments on a business loan or equipment finance are added back to calculate EBITDA. |

By working through these adjustments, you build a clear and defensible profit figure.

Meticulously identifying and documenting these add-backs is one of the most powerful things you can do. It not only helps you arrive at a fair valuation but also makes the buyer’s due diligence process significantly smoother.

Keeping your records in perfect order is absolutely essential here. To get a head start on what’s needed, it’s worth reviewing a comprehensive business tax return checklist to make sure all your paperwork is ready for inspection. This level of preparation shows you’re a professional and gives buyers the confidence they need to move forward.

Selecting the Right Valuation Method

Choosing how to value your business isn’t just about plugging numbers into a formula. It’s about finding the right lens to show a potential buyer what your company is truly worth.

Frankly, there’s no single method that works for every business. The most credible and defensible valuation comes from matching the approach to your industry, your business model, and your financial reality.

Think about it this way: you wouldn’t value a high-growth tech company the same way you’d value a trucking business with a large fleet. One is all about future earning potential; the other is tied to its tangible assets. Getting this distinction right is the first, most crucial step in arriving at a price you can stand behind.

The Income Approach: Forecasting Future Success

The Income Approach is all about potential. It answers the one question every serious buyer has: “What is this business capable of earning for me in the future?”

This makes it an excellent fit for businesses with a solid track record of stable, predictable profits. This includes established service firms, companies with recurring subscription revenue, or any operation that isn’t prone to wild swings in performance.

The most common tool in this toolkit is the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis. It sounds complex, but the concept is quite simple. You project the business’s future cash flows for a set period—usually three to five years—and then “discount” them back to what they’re worth today.

Why the discount? A dollar you might earn in five years isn’t worth the same as a dollar in your pocket right now, due to inflation and investment risk. Sophisticated buyers prefer this method because it’s forward-looking and focuses squarely on the return they can expect.

The Market Approach: Valuing Based on What’s Happening Now

The Market Approach is much more grounded in the here and now. It operates a lot like valuing a house—you look at what similar businesses in your area and industry have recently sold for. This gives you a powerful “reality check” against your own financial forecasts.

This approach relies heavily on industry multiples. A multiple is a factor that you apply to a key financial figure, most often your normalised EBITDA. So, if similar businesses in your sector are consistently selling for, say, four times their annual EBITDA, that gives you a very strong benchmark for your own valuation.

Another way to look at this is through financial multiples, like the price-to-earnings (P/E) or price-to-sales (P/S) ratios, which are worked out using data from comparable businesses. You can often find these in industry reports or obtain them from a good business broker. These multiples can vary significantly between sectors. For example, the average P/E ratio for a small retail business might be around 3.5, while for a professional services firm it could be closer to 4.2. You can find more general business indicators over at the ABS website.

A strong valuation rarely hangs its hat on just one method. The most compelling figure often comes from blending the Income and Market approaches. This shows a buyer you’ve considered both your business’s future potential and its current market value.

This blended approach creates a sensible valuation range, which is a much more powerful and flexible place to start negotiations from.

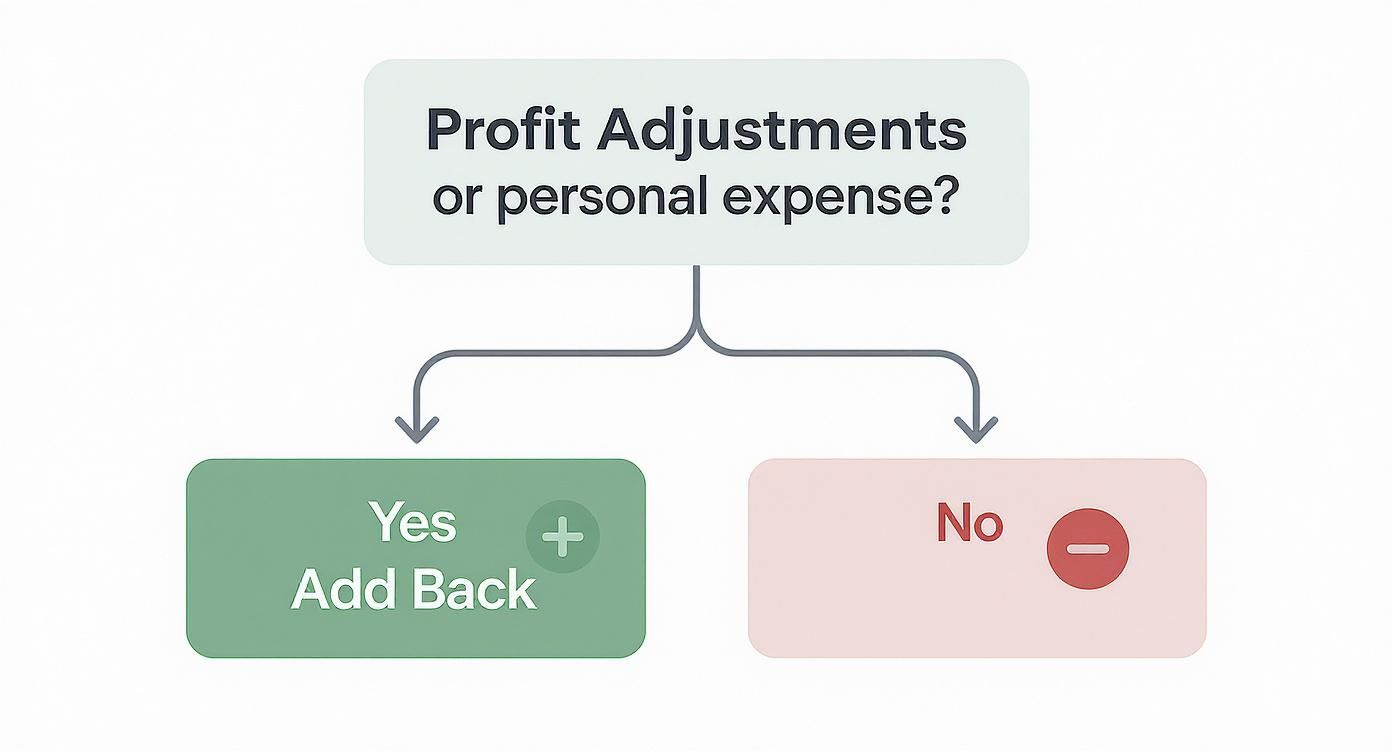

To help you figure out what to add back and what to leave in when you’re normalising your profit for these calculations, this decision tree offers a simple guide.

As you can see, the core decision really comes down to whether an expense is a legitimate, ongoing business cost or if it’s a personal or one-off item that should be added back to the profit.

The Asset-Based Approach: The Sum of the Parts

Finally, the Asset-Based Approach is the most straightforward of the lot. You simply calculate a business’s value by adding up all its assets (cash, equipment, property) and then subtracting all its liabilities (debts, accounts payable).

This method really only comes into play in a few specific situations:

- For capital-intensive businesses: Think manufacturing plants, construction firms, or logistics companies where most of the value is tied up in physical gear.

- During liquidation: If a business is being wound up, its value is simply what the assets can be sold for after every creditor has been paid.

- As a “floor” value: It can establish a minimum price, ensuring the sale at least covers the net value of its tangible assets.

For most healthy, profitable businesses, though, this method falls short. It completely ignores the intangible value you’ve spent years building—things like your brand reputation, loyal customer base, and recurring revenue streams. In many cases, those are a company’s most valuable assets.

Getting the approach right is the foundation of your entire sale process. If your business is profitable and has a good future, a blend of the Income and Market methods will almost always give you the most realistic and attractive number. If your value is tied up in what you own, the Asset-Based approach provides a crucial baseline. Understanding these options is the first step to building a valuation that truly reflects the business you’ve worked so hard to create.

Applying the Numbers to Find Your Value

Right, you’ve crunched the numbers, normalised your accounts, and picked a valuation method. Now for the exciting part – putting it all together to arrive at an actual figure. This is where we move from theory to a concrete number that will become the starting point for your asking price.

It sounds complex, but it’s really just about turning all that prep work into a tangible valuation range.

For most small to medium Australian businesses, the most common path is to take your normalised profit figure and apply an industry-standard ‘multiple’. This calculation gives you what is known as the Enterprise Value of your business.

From Normalised Profit to EBITDA

In Australian business sales, the gold standard for profit is EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation, and Amortisation). Why? Because it gives a crystal-clear picture of a company’s day-to-day operational performance, stripping out the noise from financing decisions, tax structures, or accounting choices.

Essentially, that normalised profit figure you calculated is your maintainable EBITDA. After adding back all those personal expenses and one-off costs we discussed, you’re left with the core earnings figure a potential buyer will focus on.

Let’s walk through a real-world example to make sense of this.

Case Study: The Neighbourhood Grind Cafe

Imagine you own “The Neighbourhood Grind,” a popular local café in Melbourne. You’ve had a great year, and your P&L statement is showing a net profit of $120,000. But as we know, that number doesn’t tell the full story.

Let’s apply our normalisation adjustments:

- Owner’s Salary: You paid yourself $60,000, but a fair market salary for a manager to replace you would be $90,000.

- Discretionary Expenses: That “business trip” to Bali and a few too many client dinners added up to $15,000.

- Interest on Loan: The business paid $10,000 in interest.

- Depreciation: Your accountant wrote down $25,000 for the coffee machine and kitchen fit-out.

To get to EBITDA, we start with your net profit and add back these items:

- Net Profit: $120,000

- Add back Interest: +$10,000

- Add back Depreciation: +$25,000

- Add back Discretionary Expenses: +$15,000

- Total: $170,000

From here, we have to subtract the market-rate salary for a manager ($90,000), not what you actually paid yourself.

- Normalised EBITDA = $170,000 – $90,000 = $80,000

This $80,000 normalised EBITDA is your key figure. It represents the café’s true, ongoing earning power that a new owner can reasonably expect. This is the solid foundation for our valuation.

Applying the Industry Multiple

With our EBITDA sorted, we now apply an industry multiple. Let’s say that based on recent sales of similar cafés in the area, the going rate is around 3.5x EBITDA.

The calculation for your Enterprise Value is straightforward:

- Enterprise Value = Normalised EBITDA x Industry Multiple

- Enterprise Value = $80,000 x 3.5 = $280,000

This $280,000 represents the total value of the business as an operating entity. But this isn’t the final number that lands in your bank account. We have a couple of crucial adjustments left to make.

As a side note, some owners like to think about this in terms of their desired return on investment (ROI). For instance, if your net profit was $100,000 and you wanted a minimum ROI of 50%, you’d set a floor price of $200,000. You can find more practical tips like this on the Australian government’s business resources page.

Final Adjustments for Equity Value

The Enterprise Value gives us the value of the whole business, but what you’re actually selling is the equity—your ownership stake. To find the final Equity Value, we need to account for working capital and any debt.

- Working Capital: This is the cash and inventory needed to run the business day-to-day. The sale price typically assumes a normal amount of working capital is left for the new owner. If you have excess cash sitting in the bank above this level, it gets added to the price. If there’s a shortfall, it’s deducted.

- Net Debt: Any outstanding business loans or equipment finance must be paid out from the sale proceeds. This is subtracted from the Enterprise Value.

Let’s go back to our café example one last time:

- Enterprise Value: $280,000

- Let’s assume there’s $10,000 in excess working capital (cash) in the bank account.

- The business still has an outstanding loan of $40,000.

Final Equity Value = Enterprise Value + Excess Working Capital – Net Debt

- Equity Value = $280,000 + $10,000 – $40,000 = $250,000

And there you have it. This $250,000 is the final figure—it’s what you, the seller, can expect to receive before any tax considerations. By methodically working through these steps, you’ve successfully translated a raw profit number into a defensible, market-based valuation.

Backing Up Your Price Tag with Hard Evidence

A valuation is just a number on a spreadsheet until you can prove it. Any potential buyer will scrutinise every claim you make, so your valuation is only as strong as the paperwork and market data that stands behind it. Think of it as building a watertight case for your asking price—one that has to survive the intense process of due diligence.

Without proof, your valuation is just your opinion. With it, it’s a compelling business proposition that serious buyers will take notice of.

Getting Your Ducks in a Row: The Due Diligence File

Before you even list your business, you need to pull together a professional, transparent package of documents. This isn’t just about justifying your price; it dramatically speeds up the whole process. A buyer who receives a well-organised file right from the start sees you as a credible and professional seller.

Your core document package should include:

- Financial Statements: At least three to five years of Profit & Loss statements and Balance Sheets.

- Tax Returns: The company tax returns that correspond to the same period.

- BAS Statements: All Business Activity Statements for the last few years are crucial for verifying your revenue. If you need help getting these in order, you can learn more about our Business Activity Statement and bookkeeping services.

- Asset List: A detailed schedule of every physical asset included in the sale, with notes on its condition and estimated value.

Beyond these essentials, a well-prepared Information Memorandum (IM) is your sales pitch. It tells the story of your business—its history, strengths, and potential for growth—in a way that numbers alone cannot.

The Market Reality Check

A technically perfect valuation doesn’t mean much if it’s out of touch with what the market is actually paying. This is where you need to do a critical ‘sense check’ against what’s happening in the real world. Looking at industry benchmarks and recent sales ensures your asking price isn’t just calculated correctly, but is also realistic.

Your valuation doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it’s part of a live market. Understanding current trends and what buyers are thinking is just as important as perfecting your financial model. A price that feels right for the market will get you much more interest from day one.

Keeping an eye on up-to-date data is vital. For example, the Bizval Indicator, a key measure of Australian business sale activity, reported a year-on-year increase of 6.6% for the period ending September 2023. This kind of data shows momentum in the small business market and helps confirm if your valuation is on the right track. You can find more insights in the Bizval indicator report on their website.

By combining solid internal documents with a sharp eye on the external market, you build a valuation that is both defensible and attractive. This two-pronged approach gives you the confidence to name your price and the evidence to justify it, setting you up for a much smoother negotiation and, ultimately, a successful sale.

Getting the Right People in Your Corner

While understanding your own valuation is a great first step, selling your business entirely on your own is rarely a good idea. Bringing in professionals isn’t a sign of weakness; it’s a smart, strategic move to protect the value you’ve spent years building.

More importantly, it’s about ensuring the deal is structured correctly from both a legal and tax perspective. We have seen owners handle everything themselves to save money, only to make a costly mistake with the tax implications of the sale. A small oversight can significantly shrink the amount of cash that ends up in your bank account.

Building Your A-Team

Knowing who to call, and when, is half the battle. Each expert has a specific job to do, and you might not need all of them. The key is to understand what they bring to the table so you can build the right team for your sale.

- Business Brokers: Think of these people as your sales and marketing department. A good broker knows the current market inside and out, already has a list of potential buyers, and will handle everything from listing the business to the final negotiations. This frees you up to do what’s most important: keep running the business smoothly.

- Certified Valuers: Sometimes, you need a valuation that is completely independent and legally robust. This is often the case in a partnership buyout or a particularly complex sale. A certified valuer provides an impartial, detailed report that will stand up to intense scrutiny.

- Accountants: Your accountant is arguably your most important advisor in this process. They are absolutely essential for navigating the significant financial and tax consequences of a sale and ensuring you comply with all ATO rules.

Navigating ATO Requirements

Selling your business is a major Capital Gains Tax (CGT) event. This is where professional advice isn’t just helpful—it’s invaluable. For many business owners, the final tax bill comes as a genuine shock, simply because they didn’t plan for it.

The good news is that the government offers excellent incentives through the small business CGT concessions. These aren’t loopholes; they’re official, legislated measures designed to help business owners. They can dramatically reduce, defer, or in some cases, completely eliminate the tax you owe on the sale.

Working out if you’re eligible for the small business CGT concessions before you sign on the dotted line is one of the single most important financial decisions you will ever make. Getting this wrong can literally mean leaving tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars on the table.

Eligibility hinges on factors like your business turnover and the total net value of your assets. An experienced accountant can analyse your situation and structure the sale to maximise these concessions.

Taking the time to explore your options for business sales and succession planning with a professional ensures you’re not just getting a good sale price, but that you get to keep more of it. This final step is crucial for securing your financial future.

Common Questions We Hear About Business Valuation

When you start digging into the process of valuing your business, a few crucial questions almost always pop up. Getting straight answers is the only way to move forward with confidence and make sure you’re doing everything by the book.

We’ve pulled together some of the most common queries we get from clients to give you some straightforward insights.

What’s the Biggest Mistake Owners Make?

By far, the most common error is letting emotion drive the price tag. It’s completely understandable – you’ve poured years of blood, sweat, and tears into this business. That ‘sweat equity’ feels valuable, and you can see future potential that isn’t on the books yet.

But a valuation must be grounded in commercial reality, not just feeling. To attract serious buyers and survive the scrutiny of due diligence, the price needs to be built on normalised accounts and solid market data.

This isn’t about diminishing your hard work; it’s about building a defensible business case that a buyer can get behind.

How Much Does a Professional Valuation Cost?

The cost for a professional valuation in Australia depends on the size and complexity of your business. For a small, straightforward operation, you might get a basic ‘opinion of value’ from an experienced business broker for a few thousand dollars.

But if you have a larger or more intricate business that needs a formal, detailed report, a certified valuer will naturally charge more. The best approach is to get a few quotes from qualified professionals. It lets you compare not just the cost, but the depth of the service they’re offering.

Will I Have to Pay Capital Gains Tax?

Yes, in Australia, selling your business is almost always a Capital Gains Tax (CGT) event. But this is where getting expert advice can save you a fortune.

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has several small business CGT concessions that can dramatically reduce, defer, or in some cases, completely eliminate your tax bill. Your eligibility will hinge on factors like your business turnover and total net asset value. It’s absolutely critical to talk to an accountant to see if you qualify before you sign a sale contract.

Navigating the complexities of a business sale isn’t something you should do alone. The team at Brown Hamilton Partners provides practical, clear advice based on current legislation to make sure you get the best possible outcome from your sale and meet all your obligations. Contact us today for a confidential chat about your business sale and succession planning.

Disclaimer: The information provided on this website is for general informational purposes only. Hamilton Brown Partners assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions in the content or for any actions taken based on the information provided. Always speak to us or another registered professional before acting on any information read on this website.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!